That crew was interred in graves that ended up below The Citadel's football stadium for 50 years. They never surfaced, but the sub was found weeks later and brought back to the surface. In October 1863, designer HL Hunley led another eight-man crew who planned to show how the sub operated by diving under a ship in Charleston Harbor. The submarine sank once while docked with its hatches open in August 1863, and only three of the eight men on board escaped and survived. Two scientists have spent the past 17 years collecting the crew's remains and restoring the vessel as part of a painstaking cleanup operation The Hunley was raised from the bottom of the ocean in 2000, and initially, the discovery of the submarine only seemed to deepen the mystery. Housatonic lost five seamen, but came to rest upright in 30 feet of water, which allowed the remaining crew to be rescued after climbing the rigging and deploying lifeboats. The Hunley delivered a blast from 135 pounds of black powder below the waterline at the stern of the Housatonic, sinking the Union ship in less than five minutes. The Hunley's first and last combat mission occurred during the Civil War on Feb 17, 1864, when it sank a 1,200-ton Union warship, the USS Housatonic, outside Charleston Harbour. It us likely they also suffered traumatic brain injuries from being so close to such a large blast. Shear forces would have torn apart the delicate structures where the blood supply meets the air supply, filling the lungs with blood and killing the crew instantly.

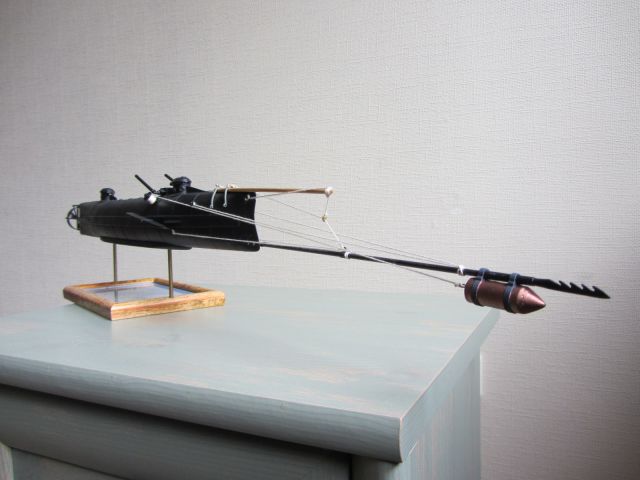

'That creates kind of a worst case scenario for the lungs.' 'When you mix these speeds together in a frothy combination like the human lungs, or hot chocolate, it combines and it ends up making the energy go slower than it would in either one,' Lance added. Lance believes that death would have been nearly instantaneous for the crew of the Hunley. 'My analysis showed that the amount of pressure ricocheting around inside the metal tube, combined with the quick rise time of the wave, would have put each member of the Hunley’s crew at a 95 percent risk of immediate, severe pulmonary trauma,' Lance wrote. The data showed that the blast wave from the explosion passed through the ship's hull and then bounced around on the inside of the cramped submarine, with enough force to be lethal. 'And like the actual Hunley, the scale-model Tiny refused to show any damage itself, even after repeated blasts, even as it transmitted the pressures inside.' I was thrilled to see that the readings looked consistent,' Lance wrote. Blast after blast, we captured and saved the waveforms. 'We set off as many charges as we could before the sun began to set on the pond. Lance slammed on the brakes and narrowly avoided being rear-ended by the truck behind her, a collision that would have likely triggered a deadly explosion.įinally, Lance was ready to carry out the experiments on her scale model of the sub, which she dubbed the CSS Tiny. The experiment nearly ended in disaster when Lance and her boyfriend were driving with 20 pounds of black powder in the trunk of her car, after a serious crash on the highway right in front of them. She also had to find a willing farmer with a pond she could use for underwater testing, since officials at Duke balked at her proposal to set off explosive charges in the retention pond on campus. Lance had to secure permission from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms to legally purchase the amount of black powder she needed for the experiment. The sub had to maneuver the torpedo against the hull of an enemy ship and detonate it while still attached to the spar. Unlike modern, self-propelled torpedoes, the Hunley's torpedo was a copper keg filled with black powder and attacked to a 16-foot spar on the bow of the submarine, Next, Lance constructed a 1/6 scale model of the Hunely and its torpedo. She constructed a precise computer model of the ship to determine its volume, and calculated that the crew would have had a 30- to 60-minute window of warning from the time the first effects of oxygen deprivation became noticeable. Lance, then a graduate student at Duke University, first had to rule out suffocation conclusively. Something that left no trace on the boat or their bones.' But that would defy human nature,' Lance wrote.

'Any of these theories would require that the crew members, with ample time to see their own deaths coming, chose to spend their last moments nobly in peace, seated at their stations. Over the years, various theories about the Hunly have been put forward, including that the ship sank due to its own torpedo or enemy weapons fire, or that the crew became trapped somehow and suffocated. Each man was still seated peacefully at his station.' 'The crew of the Hunley, however, looked quite different.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)